Historical ATP Serve & Return skills

When browsing through tennis stats (as you do…), I was surprised to find that Jeff Sackmann’s Tennis Abstract site has player serve stats – points won on first serve, second serve and so on – all the way back to the early ’90s. If you like, you can have a look at Sampras for example; the stats are shown in the far right columns of the table. I was surprised because my usual source of data, OnCourt, only has these as far back as about 2003 or so.

This made me curious about fitting a classic approach to tennis modelling to these data. The idea, perhaps first proposed by Barnett and Clarke, is to model each player as having a serve and return skill. The probability of winning a point on serve is then a function of these skills:

$p(\textrm{win_serve_point}) = \textrm{server_skill} - \textrm{returner_skill} + \textrm{intercept}$

The intercept is there to model the mean probability of winning a point on serve, which is about 62% on the ATP. In practice, it’s a little more complicated because probabilities have to be between zero and one, and the equation shown above does not ensure that. The fix is to pass the result of the right hand side through a function called the “inverse logit” function (sometimes also called the sigmoid), which makes sure that the output lies between zero and one. If you’ve heard of logistic regression, this is the exact same idea. But it’s not crucial to understanding the rest of this post.

More importantly, the serve and return skill idea gives us a rough way to categorise tennis players. One extreme type of player would be a player who is an excellent server but a poor returner – think Ivo Karlovic, for example. On the other hand, someone like David Goffin is a great returner, but a relatively poor server. Most players fall somewhere in between this spectrum. What matters for winning matches is the sum of serve and return skills. If both are high, you are both likely to break your opponent and hold serve, which is a winning combination.

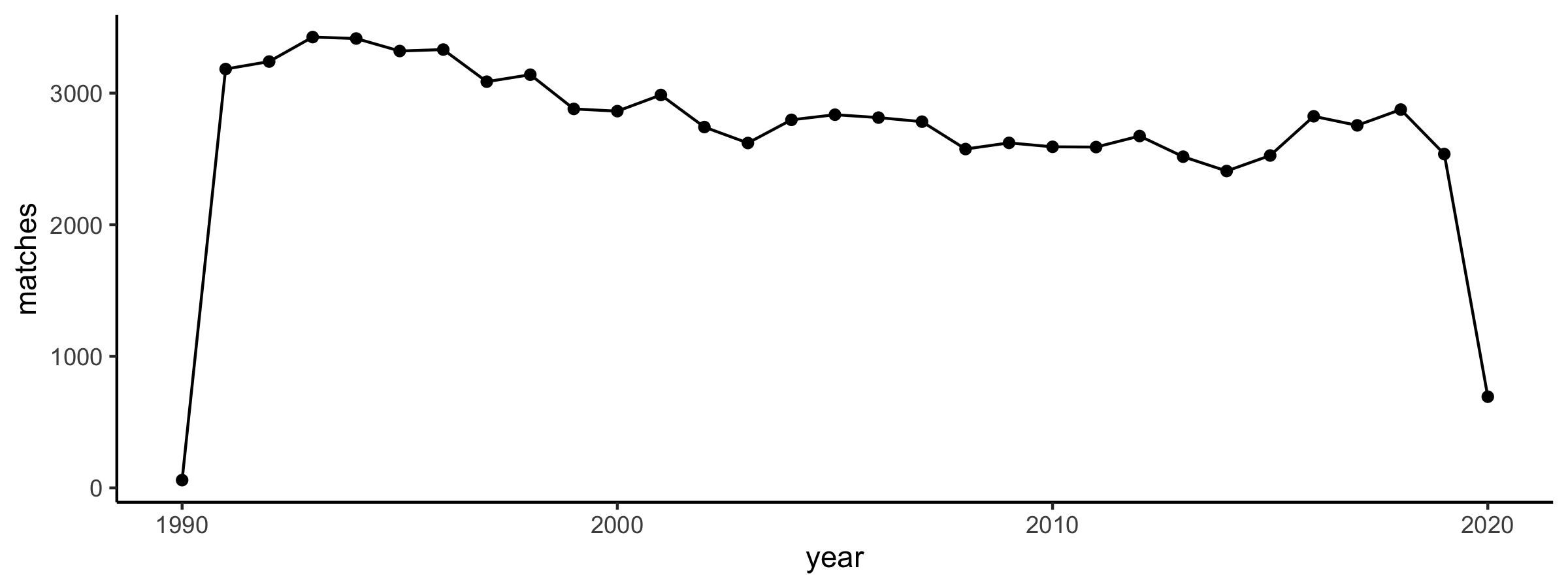

To estimate the serve and return skills, we need to know how many points each player played on serve, as well as how many they won, for each match. This is where Jeff’s data comes in: because it goes back into the early nineties, we can estimate serve and return skills all the way back. How far back? Here’s the breakdown of number of matches per year:

As you can see, the dataset (available here) starts in 1990 with a handful of matches and has between 2500 and 3500 matches per year since then. It’s quite interesting to see the numbers drop slightly over time – I’m not sure why that is, but that’s a question for another time! The drop-off in 2020, on the other hand, is easy to explain, given that the year is not over and so many tounaments are being cancelled.

The early ’90s start means that we should be able to make pretty good estimates for players from 1991 onwards. So we won’t be able to see where players like Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe land on the spectrum of serve & return skills, unfortunately, but we should be able to look at Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi, for example.

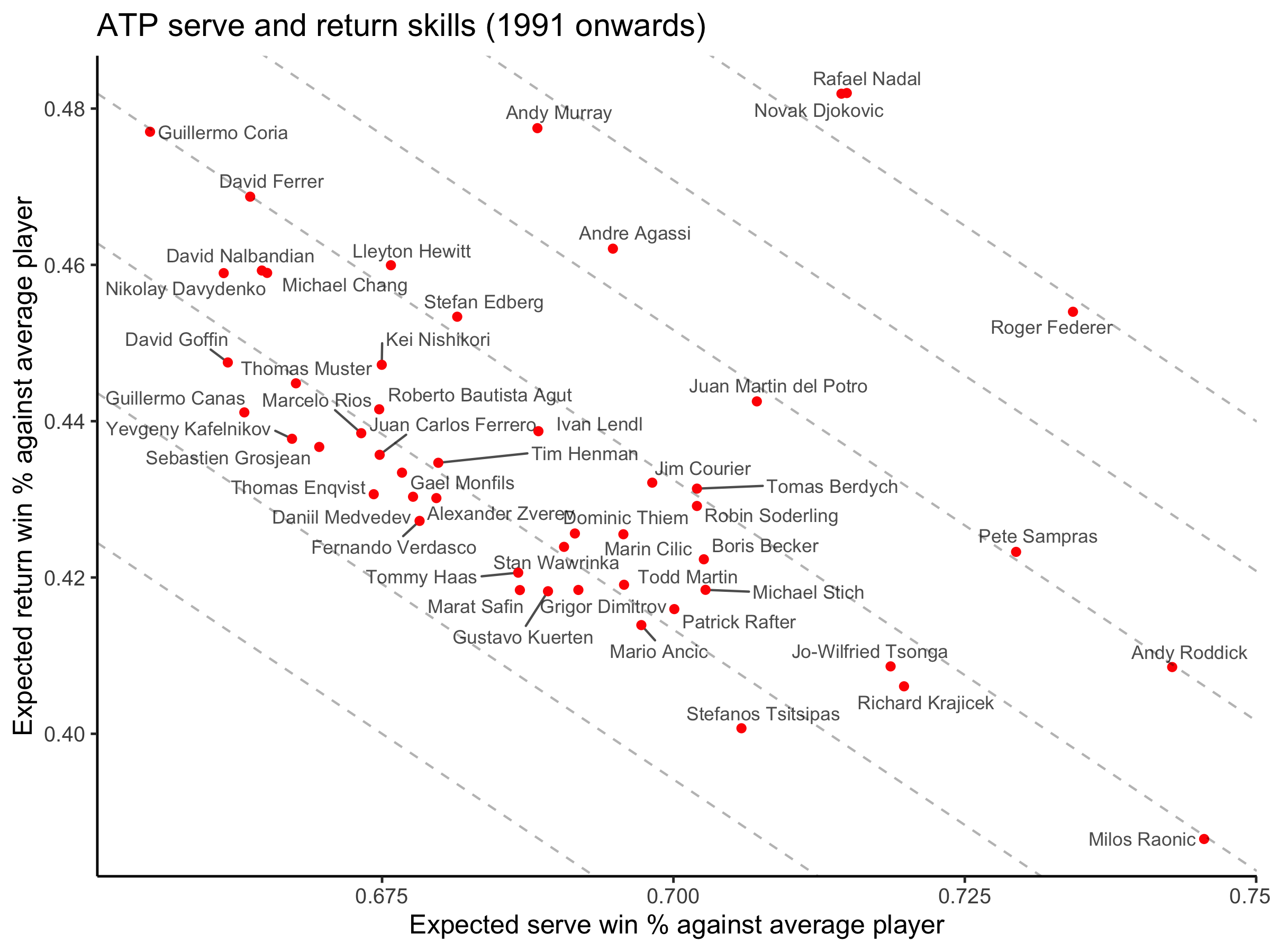

The model I fit to this dataset is fairly simple. I am just fitting a single serve and return skill per player, which means we are averaging across their entire careers, as well as across surfaces. So this should just give an overall indication, but does not necessarily represent players’ peak abilities. With that in mind, here’s the result:

The plot shows the 50 players with the highest estimated sum of serve and return skills, which should pick out the strongest players overall. To make the axes more interpretable, I converted the skills into expected performance against an average player, that is, a player with serve and return skill equal to zero.

There’s a lot to dig into. My supervisor for my Masters’ thesis, Will Knottenbelt loved these types of plots, and I think there are definitely some interesting things to see.

First off, let’s look at the extremes: Milos Raonic has the highest estimated serve skill of this group of elite players, and Guillermo Coria has the lowest. Raonic would be expected to win almost 75% of his service points against an average player, compared to around 65% for Coria. It’s interesting to see that, on the flip side, Coria is among the best returners, while Raonic is among the worst. In fact, they lie on the same dashed line: they have almost the same sum of serve and return skills.

Overall, there’s a strong negative correlation in the plot. That correlation only stands out when looking at the top players; when plotting all players, the skills look pretty uncorrelated. I’m still thinking about what that means. People have mentioned to me that some Pareto ideas might be interesting here: perhaps it’s hard to improve one aspect of a players’ game without weakening another aspect. For example, Milos Raonic’s height likely helps him serve well; if he were shorter, perhaps his return would be better, but his serve would suffer, too. Anyway, it’s something to think about!

Most players have summed serve and return skills below the line spanned by Raonic and Coria. It’s fun to see where players end up. Some players are probably unfairly rated, such as Stefan Edberg and certainly Ivan Lendl, whose best years were likely before 1991. I would have guessed Edberg to be a stronger server than he appears to be from this plot, for example.

The real elite starts with players above the Raonic - Ferrer line. First, there’s another approximate line spanning Agassi, del Potro, Sampras and Roddick, and Murray somewhat above. Sampras and Raonic are on the bigger-serving end, and Murray and Agassi on the returning end, as you might expect.

Finally, far and away, there are the big three: Federer, Djokovic and Nadal. Nadal and Djokovic occupy almost the exact same spot! They are the best returners, expected to win almost 50% of return points against an average player, and they are not far off being the best servers. Note that this is probably an imprecise way of putting it: watching them, we all know Nadal and Djokovic do not have the best serves in the game. What the model is suggesting is that they are almost as effective at winning points on serve as Richard Krajicek, likely because of what they do once the ball is in play. Federer’s summed rating is similar to Nadal and Djokovic’s. He is rated as being more effective on serve but not quite as strong on return.

Looking at the plot, one might feel bad for Roddick, del Potro and Murray, who have similar summed skill estimates as Agassi and Sampras but won “only” one (Roddick & del Potro) and three Grand Slams (Murray), respectively, compared to Agassi’s eight and Sampras’s fourteen. However, it’s important to note the limitations of the model. The skill of an average player may have shifted over the years, for example, making it hard to compare across decades. Or perhaps Agassi and Sampras had more ups and downs in their careers, averaging out to a skill that doesn’t do justice to their peak ability. In particular, Nadal, Federer and Djokovic have not retired yet and future performances might drag their averages down a bit. On the other hand, it might also just be that Federer, Djokovic and Nadal are on another level, and Roddick, del Potro and Murray were unlucky to have to face them. Whatever the case may be, I hope you enjoyed this look at some of the ATP’s best players of the last few decades.